The international publication was co-authored by Professor Christoph-Martin Geilfus, Professor Davide Francioli, and Dr. Muhammad Waqas* from the Department of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition at Hochschule Geisenheim University. Contributors from the USA, Italy, Canada, Sweden, and Australia underscore the article’s message: the call to action has global relevance, and it starts in the soil beneath our feet.

The Unsung Heroes in Our Soil

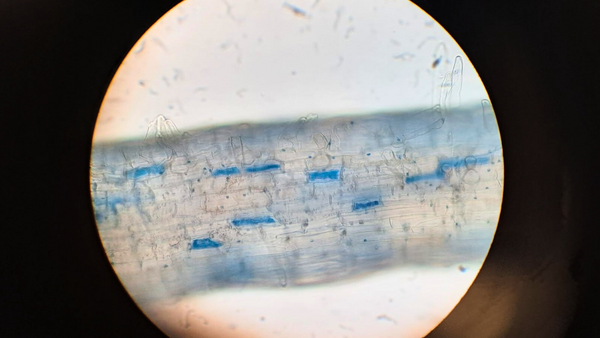

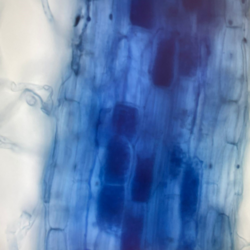

In nature, underground microorganisms such as fungi, bacteria, and other tiny life forms often form beneficial alliances with plants. These microbes help improve soil structure, enhance nutrient uptake, and suppress the spread of pathogens, thereby making a vital contribution to plant health and productivity.

These invisible helpers are not only crucial for stable ecosystems but, according to the authors, also indispensable for resilient agriculture. However, the researchers have identified a major concern: excessive fertilization, pesticides, intensive tillage, and narrow crop rotations disrupt these finely tuned interactions and drive beneficial microbes out of agricultural systems. In addition, breeding practices have often intensified this effect, as they typically focus on above-ground traits while largely ignoring the plant–microbe relationships formed below ground.

“This has received little attention until now, but if plants and soil microbes can no longer cooperate effectively, our food security is ultimately at risk,” warns Geilfus, head of the Deparment of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition in Geisenheim.

Back to the Roots: the Potential of Wild Relatives

So what exactly can be done? In their search for solutions, the authors highlight the role of wild relatives of our crops (Crop Wild Relatives, or CWR). Through thousands of years of co-evolution, many of these wild plant species and their soil microbes have adapted to each other and formed particularly beneficial symbiotic relationships.

To preserve their potential benefits for agriculture, the researchers advocate for the creation of CWR biodiversity refuges, protected areas where wild plants are conserved together with their soil microbiomes and the full range of their associated microorganisms. For long-term success, these conservation areas should be developed in close collaboration with local stakeholders.

A model example is the Parque de la Papa in Peru, where Indigenous communities work closely with the Association for Nature and Sustainable Development (ANDES) to preserve and use native potato varieties along with the microorganisms associated with them.

To systematically catalog wild plants and their microbiomes and prioritize them based on their threat level, the authors also call for the establishment and regular updating of a global ‘Red List’ of endangered CWR.

Protection and Research for More Resilient Crops

The researchers’ goal is to make cultivated plants healthier and more resilient, not through major genetic modifications, but by strengthening their collaboration with beneficial soil microorganisms. The expected benefits include more efficient nutrient uptake, greater stress tolerance, and a significant reduction in the use of chemical pesticides.

In addition to conserving wild relatives and their microbiomes, the researchers are pursuing targeted research strategies. Within the conservation areas, they plan to collect data on plants, soils, and microbial diversity and enter it into open, well-structured databases. Using artificial intelligence and advanced genetic analysis tools, they aim to identify which plant–microbe systems hold the greatest promise for future-proof agriculture.

They also see great potential in the development of synthetic microbial communities (SynComs).

Call for a Global Initiative

Given the dramatic decline in global biodiversity – which also affects CWR – the authors see urgent need for action.

“We need a global initiative as soon as possible, coordinated by international organizations such as the Crop Diversity Trust. At the same time, we need regional contact points that can work closely with local partners and tailor actions to local ecological and social conditions,” says Francioli, Professor of Plant Microbiomics at Hochschule Geisenheim University. Based on similar programs, the authors estimate the funding required for such an initiative to be in the tens of millions of euros.

Meanwhile, research at the Department of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition continues. Through complex lab and field experiments, the Geilfus and Francioli's research teams are working to better understand the functional relationships between the soil microbes of wild relatives and our cultivated crops and to unlock their potential for the agriculture of the future.

Publication

Waqas, Muhammad, McCouch, Susan R., Francioli, Davide, Tringe, Susannah G., Manzella, Daniele, Khoury, Colin K., Rieseberg, Loren H., Dempewolf, Hannes, Langridge, Peter & Geilfus, Christoph-Martin. Blueprints for sustainable plant production through the utilization of crop wild relatives and their microbiomes. Nature Communications 16, Article number: 6364 (2025).

The full article is available in Nature Communications.

*Muhammad Waqas worked on the publication as a Humboldt Research Fellow in Christoph-Martin Geilfus' team. He now works at the Xinjiang Institute of Ecology and Geography in China.